Information (noun.)

Definition: Whatever is intrepreted from a particular arrangement or sequence of things.

Also referenced as: Inform (verb) Informing (verb)

Related to: Channel, Communication, Content, Data, Information Architecture, Knowledge, Mental Model, Mess, Perception

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 12

It’s hard to shine a light on the messes we face.

It’s hard to be the one to say that something is a mess. Like a little kid standing at the edge of a dark room, we can be paralyzed by fear and not even know how to approach the mess.

These are the moments where confusion, procrastination, self-criticism, and frustration keep us from changing the world.

The first step to taming any mess is to shine a light on it so you can outline its edges and depths.

Once you brighten up your workspace, you can guide yourself through the complex journey of making sense of the mess.

I wrote this simple guidebook to help even the least experienced sensemakers tame the messes made of information (and people!) they’re sure to encounter.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 15

Things may change; the messes stay the same.

We’ve been learning how to architect information since the dawn of thought.

Page numbering, alphabetical order, indexes, lexicons, maps, and diagrams are all examples of information architecture achievements that happened well before the information age.

Even now, technology continues to change the things we make and use at a rate we don’t understand yet. But when it really comes down to it, there aren’t that many causes for confusing information.

- Too much information

- Not enough information

- Not the right information

- Some combination of these (eek!)

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 16

People architect information.

It’s easy to think about information messes as if they’re an alien attack from afar. But they’re not.

We made these messes.

When we architect information, we determine the structures we need to communicate our message.

Everything around you was architected by another person. Whether or not they were aware of what they were doing. Whether or not they did a good job. Whether or not they delegated the task to a computer.

Information is a responsibility we all share.

We’re no longer on the shore watching the information age approach; we’re up to our hips in it.

If we’re going to be successful in this new world, we need to see information as a workable material and learn to architect it in a way that gets us to our goals.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 19

Every thing has information.

Over your lifetime, you’ll make, use, maintain, consume, deliver, retrieve, receive, give, consider, develop, learn, and forget many things.

This book is a thing. Whatever you’re sitting on while reading is a thing. That thing you were thinking about a second ago? That’s a thing too.

Things come in all sorts, shapes, and sizes.

The things you’re making sense of may be analog or digital; used once or for a lifetime; made by hand or manufactured by machines.

I could have written a book about information architecture for websites or mobile applications or whatever else is trendy. Instead, I decided to focus on ways people could wrangle any mess, regardless of what it’s made of.

That’s because I believe every mess and every thing shares one important non-thing:information.

Information is whatever is conveyed or represented by a particular arrangement or sequence of things.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 20

What’s information?

Information is not a fad. It wasn’t even invented in the information age. As a concept, information is old as language and collaboration is.

The most important thing I can teach you about information is that it isn’t a thing. It’s subjective, not objective. It’s whatever a user interprets from the arrangement or sequence of things they encounter.

For example, imagine you’re looking into a bakery case. There’s one plate overflowing with oatmeal raisin cookies and another plate with a single double-chocolate chip cookie. Would you bet me a cookie that there used to be more double-chocolate chip cookies on that plate? Most people would take me up on this bet. Why? Because everything they already know tells them that there were probably more cookies on that plate.

The belief or non-belief that there were other cookies on that plate is the information each viewer interprets from the way the cookies were arranged. When we rearrange the cookies with the intent to change how people interpret them, we’re architecting information.

While we can arrange things with the intent to communicate certain information, we can’t actually make information. Our users do that for us.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 21

Information is not data or content.

Data is facts, observations, and questions about something. Content can be cookies, words, documents, images, videos, or whatever you’re arranging or sequencing.

The difference between information, data, and content is tricky, but the important point is that the absence of content or data can be just as informing as the presence.

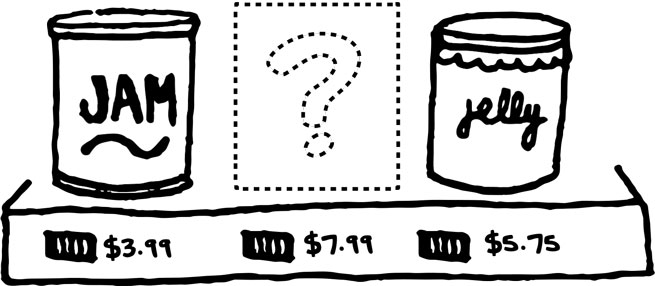

For example, if we ask two people why there is an empty spot on a grocery store shelf, one person might interpret the spot to mean that a product is sold-out, and the other might interpret it as being popular.

The jars, the jam, the price tags, and the shelf are the content. The detailed observations each person makes about these things are data. What each person encountering that shelf believes to be true about the empty spot is the information.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 23

Information is architected to serve different needs.

If you rip out the content from your favorite book and throw the words on the floor, the resulting pile is not your favorite book.

If you define each word from your favorite book and organize the definitions alphabetically, you would have a dictionary, not your favorite book.

If you arrange each word from your favorite book by gathering similarly defined words, you have a thesaurus, not your favorite book.

Neither the dictionary nor the thesaurus is anything like your favorite book, because both the architecture and the content determine how you interpret and use the resulting information.

For example, “8 of 10 Doctors Do Not Recommend” and “Doctor Recommended” are both true statements, but each serves a different intent.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 28

It’s your turn.

This chapter outlines why it’s important to identify the edges and depths of a mess, so you can lessen your anxiety and make progress.

I also introduced the need to look further than what is true, and pay attention to how users and stakeholders interpretlanguage, data, and content.

To start to identify the mess you’re facing, work through these questions:

- Users: Who are your intended users? What do you know about them? How can you get to know them better? How might they describe this mess?

- Stakeholders: Who are your stakeholders? What are their expectations? What are their thoughts about this mess? How might they describe it?

- Information: What interpretations are you dealing with? What information is being created through a lack of data or content?

- Current state: Are you dealing with too much information, not enough information, not the right information, or a combination of these?

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 53

Reality happens across channels and contexts.

A channel transmits information. A commercial on TV and YouTube is accessible on two channels. A similar message could show up in your email inbox, on a billboard, on the radio, or in the mail.

We live our lives across channels.

It’s common to see someone using a smartphone while sitting in front of a computer screen, or reading a magazine while watching TV.

As users, our context is the situation we’re in, including where we are, what we’re trying to do, how we’re feeling, and anything else that shapes our experience. Our context is always unique to us and can’t be relied upon to hold steady.

If I’m tweeting about a TV show while watching it, my context is “sitting on my couch, excited enough about what I’m watching to share my reactions.”

In this context, I’m using several different channels: Twitter, a smartphone, and TV.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 55

Reality doesn’t always fit existing patterns.

Beware of jumping into an existing solution or copying existing patterns. In my experience, too many people buy into an existing solution’s flexibility to later discover its rigidity.

Imagine trying to design a luxury fashion magazine using a technical system for grocery store coupons. The features you need may seem similar enough until you consider your context. That’s when reality sets in.

What brings whopping returns to one business might crush another. What works for kids might annoy older people. What worked five years ago may not work today.

We have to think about the effects of adopting an existing structure or language before doing so.

When architecting information, focus on your own unique objectives. You can learn from and borrow from other people. But it’s best to look at their decisions through the lens of your intended outcome.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 64

Keep it tidy.

If people judge books by their covers, they judge diagrams by their tidiness.

People use aesthetic cues to determine how legitimate, trustworthy, and useful information is. Your job is to produce a tidy representation of what you’re trying to convey without designing it too much or polishing it too early in the process.

As you make your diagram, keep your stakeholders in mind. Will they understand it? Will anything distract them? Crooked lines, misspellings, and styling mistakes lead people astray. Be careful not to add another layer of confusion to the mess.

Make it easy to make changes so you can take in feedback quickly and keep the conversation going, rather than defending or explaining the diagram.

Your diagram ultimately needs to be tidy enough for stakeholders to understand and comment on it, while being flexible enough to update.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 126

Taxonomy is how we arrange things.

When you set out to arrange something, how do you decide where the pieces go? Is it based on what looks right to you, what you believe goes together, or what someone told you to do? Or maybe you let gravity or the alphabet determine the order?

To effectively arrange anything, we have to choose methods for organizing and classifying content in ways that convey the intended information to our intended users.

Structural methods for organization and classification are called taxonomy.

Common examples of taxonomies include:

- The scientific classification for plants, animals, minerals, and other organisms

- The Dewey Decimal system for libraries

- Navigational tabs on a website

- Organizational charts showing management and team structures

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 134

Humans are complex.

Tomatoes are scientifically classified as a fruit. Some people know this and some don’t. The tomato is a great example of the vast disagreements humans have with established exact classifications.

Our mental models shape our behavior and how we relate to information.

In the case of the tomato, there are clearly differences between what science classifies as a fruit and what humans consider appropriate for fruit salad.

If you owned an online grocery service, would you dare to only list tomatoes as fruit?

Sure, you could avoid the fruit or vegetable debate entirely by classifying everything as “produce,” or you could list tomatoes in “fruit” and “vegetables.”

But what if I told you that squash, olives, cucumbers, avocados, eggplant, peppers, and okra are also fruits that are commonly mistaken as vegetables?

What do we even mean when we say “fruit” or “vegetable” in casual conversations? Classification systems can be unhelpful and indistinguishable when you’re sorting things for a particular context.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 142

Most things need a mix of taxonomic approaches.

The world is organized in seemingly endless ways, but in reality, every form can be broken down into some taxonomic patterns.

Hierarchy, heterarchy, sequence, and hypertext are just a few common patterns. Most forms involve more than one of these.

A typical website has a hierarchical navigation system, a sequence for signing up or interacting with content, and hypertext links to related content.

A typical grocery store has a hierarchical aisle system, a heterarchical database for the clerk to retrieve product information by scanning a barcode, and sequences for checking out and other basic customer service tasks. I was even in a grocery store recently where each cart had a list of the aisle locations of the 25 most common products. A great use of hypertext.

A typical book has a sequence-based narrative, a hierarchical table of contents, and a set of facets allowing it to be retrieved with either the Dewey Decimal system at a library, or within a genre-based hierarchical system used in bookstores and websites like Amazon.com.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 153

We serve many masters.

No matter what the mess is made of, we have many masters, versions of reality, and needs to serve. Information is full of history and preconceptions.

Stakeholders need to:

- Know where the project is headed

- See patterns and potential outcomes

- Frame the appropriate solution for users

Users need to:

- Know how to get around

- Have a sense of what’s possible based on their needs and expectations

- Understand the intended meaning

It’s our job to uncover subjective reality.

An important part of that is identifying the differences between what stakeholders think users need and what users think they need for themselves.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 154

Make room for information architecture.

If you find yourself needing to promote this practice, here are some ways you can talk about it:

You: “Wow, we have lots of information floating around about this, huh?”

Them: “It’s a bit unruly, isn’t it?”

You: “Yeah, I think I can help though. I recently learned about the practice of information architecture. Have you heard of it?”

Them: “Never heard of it. What is it?”

You: “It’s the practice of deciding which structures we need so our intent comes through to users.”

Them: “Is it hard? Do we need an expert?”

You: “Well, it isn’t hard if we’re willing to collaborate and make decisions about what we’re doing. I have some tools we can try. What do you think?”