Measure (verb.)

Definition: Ascertain the size, amount, or degree of something.

Also referenced as: Measure (verb) Measurement (noun) Measurements (noun) Measures (verb) Measureable (adjective) Measured (adjective)

Related to: Baseline, Data, Flag, Intent, Purpose, Reflection

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 41

How varies widely.

The saying “there are many ways to skin a cat” reminds us that we have options when it comes to achieving our intent. There are many ways to do just about anything

Whether you’re working on a museum exhibit, a news article, or a grocery store, you should explore all of your options before choosing a direction.

How is an ever-growing list of directions we could take while staying true to our reasons why.

To look at your options, ask yourself:

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 69

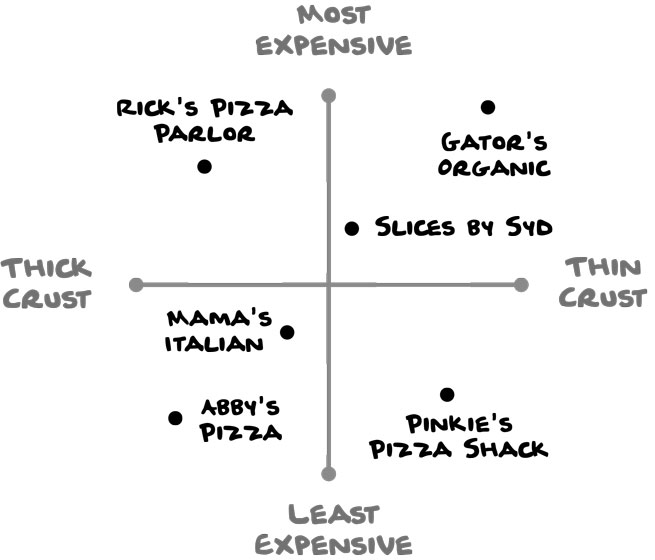

4. Quadrant Diagram

A quadrant diagram illustrates how things compare to one another. You can create one based on exact data (e.g., price of a slice, thickness of pizza-crust) or ambiguous data (e.g., fancy or casual, quality of service, or tastiness).

This diagram would be more exact with prices and crust measurements. (But how do you properly measure the thickness of pizza crust anyways?)

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 100

Watch out for options and opinions.

When we talk about what something has to do, we sometimes answer with options of what it could do or opinions of what it should do.

A strong requirement describes the results you want without outlining how to get there.

A weak requirement might be written as: “A user is able to easily publish an article with one click of a button.” This simple sentence implies the interaction (one click), the interface (a button), and introduces an ambiguous measurement of quality (easily).

When we introduce implications and ambiguity into the process, we can unknowingly lock ourselves into decisions we don’t mean to make.

As an example, I once had a client ask for a “homepage made of buttons, not just text.” He had no idea that, to a web designer, a button is the way a user submits a form online. To my client, the word button meant he could change the content over time as his business changes.

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 108

There’s distance between reality and your intent.

Your intent shows you what you want to become when you’re all grown up. But intent alone won’t get things done.

Breaking your intent into specific goals helps you to figure out where to invest your time and energy, and how to measure your progress along the way.

A goal is something specific that you want to do. A well-defined goal has the following elements:

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 109

Goals are our lens on the world.

Goals change what’s possible and what happens next.

Whether big or small, for today or this year, goals change how you spend time and resources.

The ways you set and measure goals affects how you define a good day or a bad day, valuable partners or the competition, productive time or a waste of time.

Goals are only reachable when you’re being realistic about the distance between reality and where you want to go. You may measure that distance in time, money, politics, talent, or technology.

Once you figure out the distance you need to travel, momentum can replace the anxiety of not knowing how to move forward.

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 110

Progress is as important to measure as success.

Many projects are more manageable if you cut them into smaller tasks. Sequencing those tasks can mean moving through a tangled web of dependencies.

A dependency is a condition that has to be in place for something to happen. For example, the links throughout this book are dependent on me publishing the content.

How you choose to measure progress can affect the likelihood of your success. Choose a measurement that reinforces your intent. For example:

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 111

Indicators help us measure progress.

Most things can be measured by systems or people.

Indicators tell you if you’re moving towards your intent or away from it. A business might use averages like dollars per order or call response time as indicators of how well they’re doing.

It’s not always easy to figure out how to measure things, but if you’re persistent, you can gain invaluable insights about your progress.

The good news is the work it takes to define and measure indicators is almost always worth the effort.

To find the right indicators, start with these questions:

- What can you measure in your world?

- What could you measure if things changed?

- What signs would tell you if you’re moving towards or away from your intent?

Examples of indicators follow.

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 112

Common indicators.

- Satisfaction: Are customers happy with what you’re delivering against your promises?

- Kudos: How often do people praise you for your efforts or contributions?

- Profit: How much was left over after expenses?

- Value: What would someone pay for it?

- Loyalty: How likely are your users to return?

- Traffic: How many people used, visited, or saw what you made?

- Conversion: What percentage of people acted the way you hoped they would?

- Spread: How fast is word getting around about what you’re doing?

- Perception: What do people believe about what you’re making or trying to achieve?

- Competition: Who has similar intents to yours?

- Complaints: How many users are reaching out about an aspect of your product or service?

- Backlash: What negative commentary do you receive or expect?

- Expenses: How much did you spend?

- Debt: How much do you owe?

- Lost time: How many minutes, hours, or days did you spend unnecessarily?

- Drop-off: How many people leave without taking the action you hoped they would?

- Waste: How much do you discard, measured in materials and time?

- Murk: What alternative truths or opinions exist about what you’re making or trying to achieve?

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 115

Baselines help us stay in touch with reality.

The first step in understanding how something is performing is to measure it as it is.

A baseline is the measurement of something before changing it. Without baselines, assumptions will likely lead us in the wrong direction.

Here are two examples:

- If a prominent department store saw quarterly profits increase by $1.5M after their Super Bowl ad, the ad may be seen as effective. But if the baseline of regular quarterly profit increase for this brand is typically $5.5M+ after a Super Bowl ad, we’d judge the ad differently.

- Imagine an elementary school is reporting test scores averaging in the C+ range for the majority of their students. This may seem unimpressive, or even worrisome, until our baseline is introduced: average test scores this time last year were a D+.

When we have a baseline, we can judge performance. Without that, we may mistake the ad as successful and the teachers as incapable.

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 117

Measurements have rhythm.

Some things are best measured moment to moment. Others are best measured over weeks, months, years, or even decades.

The right rhythm depends on your context and your intent. When you’re choosing a rhythm, think about the ways you collect data, how specific it needs to be, and how complex it is.

Consider these factors:

- Timeframe: Is this measurement most useful after one hour, one day, a season, a year, or an entire decade? What’s a better baseline: yesterday, last month, a year ago, or twenty years ago?

- Access: Is the data readily available? Or does it require help from a particular person or system?

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 118

Fuzzy is normal.

What is good for one person can be profoundly bad for another, even if their goal is roughly the same. We each live within a unique set of contradictions and experiences that shape how we see the world.

Remember that there’s no right or wrong way to do something. Words like right and wrong are subjective.

The important part is being honest about what you intend to accomplish within the complicated reality of your life. Your intent may differ from other people; you may perceive things differently.

You may be dealing with an indicator that’s surprisingly difficult to measure, a data source that’s grossly unreliable, or a perceptual baseline that’s impossible to back up with data.

But as fuzzy as your lens can seem, setting goals with incomplete data is still a good way to determine if you’re moving in the right direction.

Uncertainty comes up in almost every project. But you can only learn from those moments if you don’t give up. Stick with the tasks that help you clarify and measure the distance ahead.

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 119

Meet Jim.

Jim owns a retail store. His profits and traffic have been declining for the last few years. His employees are convinced that, to save the business, the company website needs to let people buy things online. But all Jim sees is more complications, more people to manage, and more expenses. He thinks, “If we sell on the website, we have to take photos, and pack and ship each order. Who will do that?”

With rent going up and profits going down, Jim isn’t sure if changing the website will save his business. He doesn’t know the distance he needs to travel to get to his goal. He wonders, “Will improving my website even help? Or will it just make things worse?”

To think through this decision, Jim:

- Makes a list of indicators to measure the store

- Measures the baseline for each indicator

- Sets up flags that keep him informed of changes

- Identifies ways to improve towards his goals

If Jim’s goal is to increase in-store traffic and reduce expenses, an online store probably doesn’t make as much sense as other things he could do.

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 120

Set your goals.

Think about what you’re trying to accomplish.

- Revisit what you intend to do and why. Now break it down into specific goals.

- Make a dream list of what would be measureable in an ideal world. Even if the measurement is fuzzy or hard to find, it’s useful to think about the best-case scenario.

- Remember to mine data from people.

- Measure the baseline of what you can. Once you have your dream list, narrow it down to an achievable set of measurements to gather a baseline reading of.

- Make a list of indicators to potentially measure.

- List some situations where you’d want to be notified if things change. Then, figure out how to make those flags for yourself.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 160

Make sense yet?

- Have you explored the depth and edges of the mess that you face?

- Do you know why you have the intent you have and what it means to how you will solve your problem?

- Have you faced reality and thought about contexts and channels your users could be in?

- What language have you chosen to use to clarify your direction?

- What specific goals and baselines will you measure your progress against?

- Have you put together various structures and tested them to make sure your intended message comes through to users?

- Are you prepared to adjust?